I have been trying to dabble in non-fiction a bit more, and I’ve always had an interest in notable crimes and their aftermath. Regarding school-related crimes and shootings, none is more noteworthy than the 1999 Columbine High School Massacre (often referred to simply as ‘Columbine’).

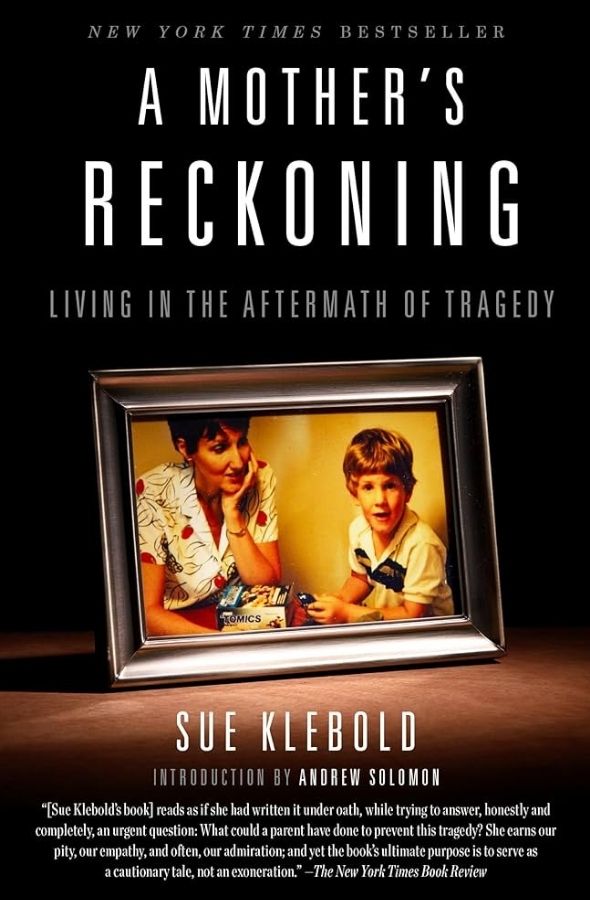

In A Mother’s Reckoning, Sue Klebold, mother of co-shooter Dylan Klebold, details much of the aftermath and the family’s personal struggle with reconciling and accepting how their son/sibling could assist in the murder of thirteen people, before taking his own life.

It details from the day the tragedy happened, and much of the years that followed prior to the memoir’s publication. Klebold also includes various family stories and good memories, as well as some that worry her in retrospect, that occurred prior to the massacre in April. Moreover, there are plenty of stories about her son’s friends and mention of their relationship to the Klebold family (but these are typically only as context or expansions on stories about Dylan).

These moments are when the memoir is at its best and remains on topic about the Klebold family and the tragedy, as well as its effects on others. It helps aids in highlighting how easily the warning signs were missed by those around either killer, whilst also indicating how we delude ourselves into believing we know the true nature of a person we love.

Naturally, there is a deep level of sensitivity and gentility baked into the memoir. Some of the stories shared feel invasive and incredibly private, but never over-the-top or something that should worry anyone under normal circumstances… unless it’s about some of Dylan’s more aggressive or criminal behaviour, which obviously come under the umbrella of being a warning sign for what was to come.

It is only when we realise that we are talking about the living days of a now dead mass murder—told by a mother who feels a heavy amount of guilt for what her son did, and what she failed to prevent—that these things feel more heavy, significant, and potentially obvious in the showcase of worrying behaviour. Yet, it still feels like much is left out, even when these details and family pictures are included, as though Klebold has hand-picked much of what she shares.

My biggest criticism is that this book is really something written by the author for the author. Klebold, as an understandably hurt and still grieving mother, tends to ramble on much about suicide and the importance of ‘brain health’ within every person’s life. The events of Columbine, as she notes, helped her find her purpose with aiding in suicide prevention and helping others understand the signs of depressive and destructive behaviour before it culminates in tragedy.

It’s a noble cause, but I found my eyes glazing over when Klebold had yet another tangent to go on, another lecture if you will. Multiple experts she met across the years are discussed and quoted within this memoir, as are various articles and studies, alongside other people’s own personal grief they shared with the author during an event or meeting. I had to wonder if I was reading a memoir or a textbook about suicide and mental health at some point, because you can take selective sections of this (auto)biographical memoir and find no significant mention or relation to Columbine, just facts about psyche and influences.

I suppose another criticism is that some details surrounding the massacre—the one her son played a large role in—are wrong or inaccurate, creating a somewhat misleading narrative about Klebold’s son and the context surrounding the shooting. By no means am I an expert on, or avid researcher of, Columbine and other shootings (at least not at the time of writing). Yet, when Klebold references Dylan being shoved in one of the home tapes released, I can’t help but be aware that it was Eric Veik, behind the camera following Eric Harris around, that was shoved on tape. Dylan Klebold is seen at the very end of the video, several minutes after the event. So, unless Klebold is referring to a totally different video that never surfaced, it shows she does not have the most accurate grasp of things, even those with literal visual evidence that would only take a few minutes to confirm.

Furthermore, Klebold also reports her son’s nickname/alias as ‘VoDKa’ (remarking that the DK represent his initials), when in all his writings Dylan instead formats this name as ‘VoDkA’. This is not a significant detail, but it is a sign of easy-to-research matters being reported straight from personal memory, rather than evidence surrounding the Columbine case and Dylan himself. Alternatively, it could suggest that Klebold does not want to, or is maybe emotionally incapable of, sifting through footage and journal entries involving her son—but I doubt that, given she wrote a memoir that would only generate or revive interest in Columbine and her murderous son.

Speaking of Klebold’s grasp on things, I feel referring to ‘fifteen victims’ is in bad taste. I understand that Klebold is viewing the two murderers as victims of mood disorders, rejection, troubled school culture, gun access, and a system that seemingly failed to catch or fix them.

The shooters were victims, in a way, but they were not victims of their actions—they had always known death was the only thing that followed their rampage, they had planned to die by officer or suicide, so I fail to see how they can be victims of themselves in that context. Given that their deaths were a premeditated, intentional end to their actions, it feels crude and insensitive to align them with the thirteen lives they took on their destructive way out. A mass shooter cannot be considered a true victim of their own act of terror, the same way one would hardly sympathise with a suicide bomber.

Additionally, partly chucking blame at things such as violent video games and films, or even shifting a large amount of blame onto co-shooter Eric Harris (who was much more externally angry) creates an image of Dylan as a depressed follower. Although Klebold does not excuse her son for a moment and acknowledges him as a ‘willing participant’, there are still hints of a mother trying to avoid relegating total blame onto her son; that he had his negative aspects and ‘potential’ mood disorders manipulated by his friend Eric, and participated more as a means of ending his life, both of which are debatable and hard to confirm. However, the suicide motive is more believable than any manipulation or blackmail conspiracy by Harris.

I don’t blame the Klebold family for their son’s actions, nor could anyone have expected them to know what he was planning. With such a volatile subject, about such a monstrous and disturbed person, it’s hard to conclude whether this memoir is trying to soften the image around her son. Plenty of those who knew him describe him similarly, as a gentle, shy, and funny boy. One full of good morals and potential, with a love for baseball and working in theatre productions.

However, I don’t think noting that the ‘at least four occasions’ he spared someone during the shooting is reflective that he had ‘good’ elements left in him by the day of the massacre.

Klebold can defend her son in the events prior to the massacre, but a few instances of mercy in a hate-filled event—a failed bombing designed to kill hundreds in a propane inferno, turned to an impromptu shooting after failed detonations—does not feel like appropriate material to suggest Dylan possessed any sanity or morals during the shooting. Furthermore, even if he did possess sanity and morals, and was mostly of sound mind, it almost makes it more monstrous that he willingly planned and participated in such an event, consensually riddling school children with lead only to be championed by his mother as still possessing ‘good’ within him.

My recommendation is mixed, because it’s such a niche topic and will leave every reader feeling different based on their own morals, politics, and awareness of the incident. Sue Klebold’s logic, though, is certainly the most flawed element.

Those who know nothing about Columbine and take Klebold’s word as fact will be misled, and those who know more about the massacre will see when Klebold is trying to mask or redirect some blame away from her son. And, like I said, the memoir often sidetracks into lecturing and throwing around facts and statistics, which is ironic with all the minor errors and misreports included, alongside Klebold’s unwillingness to accept the fact her son was a bloodthirsty killer, even if only for the hour the attack played out.

These facts and things Klebold points to throughout her book may help to indicate how and why Dylan’s depression and suicidal nature led to him committing such actions with his friend. But, ultimately, statistics don’t excuse his role, nor does the follower-leader dynamic Klebold occasionally tries to paint between her son and his fatal friend.

If you have an interest in Columbine, true crime, or suicide activism, then certainly give this memoir a read. If you don’t have any interest in those things, you are most likely going to find little value in reading this book. Without some mental and ethical preparation, you may even risk trivialising its details and timeline of events into nothing more than a dramatic tale of depression, murder, and all-round loss.

Ultimately, it is an interesting exploration, and perhaps just did not take the angle and viewpoint I had hoped it would… or the moral one, for that matter. There is good and bad authoring present, but I suppose we cannot expect a mother so destroyed by guilt and grief to be unbiased or sound in everything she assesses and recalls, but there are limits to those exceptions.

The (sometimes blatant) misinformation within this memoir, as well as a subtle sense of questionable victimisation on Klebold’s part, can damage how people view her, Columbine, and the mass shooter that is her son. It also does not help that she allegedly published this book against the wishes of her now ex-husband and her remaining son, furthering the personal politics that surround this memoir. One wonders what its publication really achieved in the end, bar glimpsing more into the life of a school shooter and his family.

Because of the misinformation and inconsistent blamelessness, it fails to get a great review score, despite being a rather captivating piece of writing. It remains recommendable, so long as you go into it with knowledge that it is not an entirely factual or unbiased account of pre- and post-April 1999. Klebold did donate the proceeds to mental health and suicide-related charities, too, so that element is commendable, but meddling with facts and trying to obfuscate reality is not. So, a cautious recommendation from me to those not so easily led or naive.

Leave a Reply